6

Yajurveda

MANTRAS of the Rigveda are all in poetic form. But Yajurveda is principally in prose form. The word "Yajus" is derived from the root "Yaj," which means to consecrate, to offer, to sacrifice. The mantras of Yajurveda are, therefore, devoted to acts of sacrifice.

Sacrifice is understood primarily in its ritualistic sense, and Yajurveda itself speaks of various kinds of ritualistic sacrifices. Rituals of various sacrifices were laid down in detail and they are expected to be performed with meticulous care. There is a belief among ritualists that the rites, if properly performed, are effective and produce desired results. The important rites are related to sacrifices called "Chaturmasya", "Vajapeya", "Ashwamedha" and "Rajasuya".

But apart from the ritualistic meaning, sacrifice has also an inner meaning. It is this inner meaning which is extremely important. Every action is inwardly a sacrifice, if

page–43

it is done as an offering to the Divine. All inner offering is received by the Divine, and the Divine receives by Himself offering something of His divine nature to the doer of action. When this process of offering of the doer and the offering of the Divine in the act of receiving is repeated again and again, in every act, in every manner of being, the Divine begins to take charge of the doer and, eventually, the doer is transformed into the Divine Worker; he becomes the channel of the Divine Will. The ultimate result that ensues is the occurrence of the Divine Event, with all its splendour, glory, miraculousness and incalculable consequence for the world.

The Yajurveda is fundamentally the secret science of the Divine Events, which can alter what is preplanned or predestined by the power of human will, human action. Karma. The basic teaching of the Yajurveda is that Karma can be altered, that humanly destined events can be prevented, modified, transformed by means of intense processes of inner sacrifice.

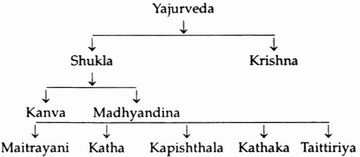

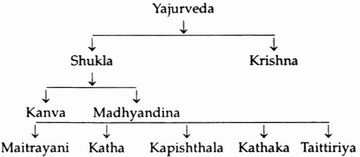

There are two main versions of the Yajurveda: Shukia Yajurveda and Krishna Yajurveda. At one time, there were 101 Shakhas or branches of it. But over centuries, most of them have become extinct, and we have only the following Shakhas as shown in the table given as under:

page–44

The Vajasaneyi Yajurveda has 40 chapters; it has 29,625 words, and 88,875 letters. More than one third of the mantras of the Yajurveda have been taken from Rigveda. The last chapter of the Shukia Yajurveda is the famous Ishavasya Upanishad, to which we have made reference earlier. But as this Upanishad is very important, we may give briefly an idea of its main contents.

Isha Upanishad has eighteen mantras. Its main message is contained in the following:

![]()

"By that renounced, thou shouldst enjoy."

This Upanishad has four movements:

In the first, it is declared that the entire universe is inhabited by the Spirit. On that basis, the rule of a divine life for man is founded,—enjoyment of all by renunciation of all through the exclusion of desire. There is then declared the justification of works and the physical life.

In the second movement, the basis of fulfilment of the rule of life are found in the experience of unity by which man identifies himself with the cosmic and transcendental self and with all its becomings, but with an entire freedom from grief and illusion.

In the third movement, vidya and avidya, Knowledge and Ignorance are reconciled by their mutual utility to the progressive self-realisation which proceeds from the state of mortality to the state of immortality.

In the fourth movement, the relation of Supreme Truth and Immortality and the activities of the life are symbolically indicated.

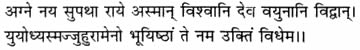

The prayer to Agni, which is given in the last mantra of this chapter is very famous. It runs as follows:

page–45

"0 Agni, Being of Illumined Will, knowing all things that are manifested, lead us by the good path to the felicity; remove from us the devious attraction of sin. To thee completes! speech of submission we dispose.

page–46

7

Yajurveda (contd)

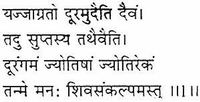

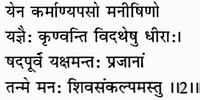

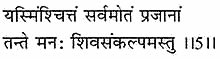

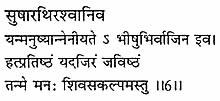

WE shall now refer to a few verses of the Yajurveda. These verses are devoted to the fostering of Good Will in our consciousness. These are six verses, which all end with the phrase: "tanme manah shiva samkalpamastu" (may that mind of mine be filled with Good Will). These verses are as follows:

"The mind, irrespective of whether one is awake or asleep, travels to far distant corners; this far distant-moving mind is the light of lights.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

Page–47

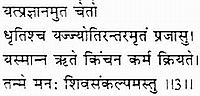

"It is by virtue of this mind that the enlightened ones, endowed with deep insight and operative skill, perform actions as a sacrifice; the mind is extraordinary, highly dynamic and effective, hidden with creative powers.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

"The mind represents insight and awareness, patience, light and nectar (or immortal light) within the human beings; without mind no action can be performed.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

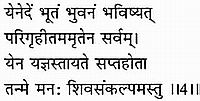

"That immortal mind penetrates all the past, the present and the future; the mind itself extends into all actions of sacrifice endowed with seven sacrifices.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

Page–48

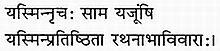

"The mind is the receptacle of the Rigveda, Samaveda and Yajurveda; they are located in it just as spokes are contained in the centre of the wheel of a chariot; all the stuff of consciousness of all the beings is interlocked in it.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

"As an expert charioteer mobilises the horses with the reins, so does the mind mobilise human beings. It is the most dynamic and fast moving (director) located in the heart.

May that mind of mine be filled with Good Will."

The above verses indicate the great significance that has been attached to Good Will in the Veda. We speak today of the imperative need of harmony, but it is not sufficiently realised that the only stable foundation of harmony is good will from oneself and good will from others. Considering that all problems of human existence are essentially problems of harmony, it is obvious that generation of Good Will is the most important task in the world.

We may also note that these verses are universal in character; they do not postulate any religious belief; they do not favour any particular group or community; they do not limit goodwill to any country or race; they express an unconditional aspiration for good will for all and for all time.

The prayer contained in these verses, thus, transcends all narrow interests and can be offered by any human being

Page–49

who sincerely wishes to express his or her humane, ethical and spiritual aspiration to grow in purity, harmony and universality.

Another important element to be noted in these verses is the profundity of knowledge that they contain about the nature of human consciousness. They describe briefly but quite comprehensively the nature and powers of the human mind. This description is an important part of the Vedic science of psychology. Let us dwell a little more on this point.

The Veda uses the word "ananas" with a special meaning in these verses. In the Gayatri mantra that we had studied earlier, the important word that was used was dhi. In other verses, the Veda speaks of medha; in some others, it speaks of chitta; in still some others, it speaks of buddhi or prajna. The distinction between medha and buddhi is that while medha is dependent on sensations in its function of understanding, buddhi operates from above the sensation and can arrive at a judgment which may even contradict the evidence of sensation. Buddhi is the same as dhi, or prajna. But, is buddhi different or distinguishable from manas? If so, what is that difference?

Manas, as used in these Vedic verses, is a larger term. It has, first, the basic function of co-ordinating the activities of all our senses, viz., hearing, touch, seeing, tasting and smelling. In fact, manas is regarded as the real sense, and other senses give us sense-experiences only when they are connected with manas. That is why when we sleep, and when our manas is withdrawn from sensory functions like hearing, we do not sense anything even when objects impinge on our senses. If our sleep is deep, we do not hear even a loud noise. That is because the sense of hearing has for the time being got dissociated from manas.

Page–50

Manas as a co-ordinator of senses or as itself a sense forms the lowest layer of our inner being; there are higher layers also. Manas can, in its higher functioning, develop senses other than the normal five senses of which we are normally aware. For example, we do not normally, have the sense of weighing the volume of an object. But manas can develop this sense. Manas can also see even when eyes are blindfolded. It can touch even without contact with the skin. It can even hear without the use of ordinary sense of hearing. How, for example, do we see objects in our dreams when our outer eyes are closed? We all hear, touch and smell in our dreams. How does it happen? The Vedic Science of Psychology tells us that this happens because of the activities of manas. As it declares:

"The mind or manas, irrespective of whether one is awake or asleep, travels to far distant corners; this far-distant moving mind is the light of lights."

At a still deeper level, we find that the psychological powers of manas can be expanded. These expansions can be effected by concentration of consciousness, by dhyana and samadhi. In these expansions, we reach a level, which is that of subliminal mental consciousness. The Vedic psychology tells us that the powers of the subliminal mental consciousness include the following:

(a) deep insight (independence of reasoning);

(b) operative skill (independence of learning or practice);

(c) light of clarity (experienced often as sudden flashes);

(d) knowledge of the past, present and future (often experienced as premonitions, warnings, visions of the future in dreams or in waking state or in trance); and

Page–51

(e) impulsion to action (based upon inner feeling, irresistible force of action, independence of one's prudent calculations or reasoning.)

In modern developments of psychology, all these powers are now being gradually recognised. But we see that these powers were already described in the Veda, and they were attributed to the mind, manas, as we see in the verses given above.

But at this stage, a question arises. Does the manas, with all these extraordinary powers, still need to be oriented towards Good Will? Why so? Is Good Will not automatic to manas? The answer is, no. For subliminal consciousness, although wide and complex, and endowed with light and extraordinary powers, is not the highest consciousness; it is not truth-consciousness either. According to the Veda, there are levels and states, higher and better than those of manas. Veda recognises four faculties of consciousness higher than the mental ones. They have been named. Revelation (Ila); Inspiration (Saraswati); Intuition (Sarama) and Discrimination (Daksha). And, above these four is the faculty of Rita-chit. It is only in Rita-chit that Goodwill is automatic. At all levels lower than the Rita-chit, there is the need to orient towards Good-Will by exercise of effort, by tapasya, or by prayer or aspiration.

This is the real rationale behind the prayer that is contained in the abovecited verses. These verses provide a good example of how the Veda contains psychological knowledge as also the method of its application. They describe mental states; they show their wide powers; they also describe their limitations; they also prescribe how these powers, wide but limited, can be oriented towards dimension of Good Will; they even have the mantras, by repetition of which, one can enter into that dimension and

Page–52

be filled with the powers of it.

In conclusion, we might make the following observations:

1. In Vedic Psychology, there is the cognisance of a state of consciousness where knowledge and will are unified. In that state, there is no conflict between what is known and what is done. If there is the knowledge of the Right, there will also be the Will for the Right and Right Action will follow. That state of consciousness is known in the Veda as Rita- chit. It is also connected with another Vedic phrase: kavikratu. Kavi means the one who knows, one who is wise. Kratu means the Will to action. Kavikratu thus means the Will to action in accordance with the knowledge or wisdom.

2. At lower levels of consciousness, there is bifurcation between Knowledge and Will; there is also decreasing luminosity of knowledge and increasing infirmity of Will, as one goes down to lower and lower levels of consciousness.

3. At the lowest level, there is inconscience; there knowledge is thickly veiled. There is only unintelligent Will or action.

4. In the ascending scale, there is material consciousness, vital consciousness, mental consciousness, and still higher levels of consciousness until one reaches the highest levels of consciousness where Knowledge and Action are united as in Rita- chit.

5. Mental consciousness is the middle point in this series. The verses, given here, place before us a vivid picture of this mental consciousness, manas.

Page–53

At this level, there are degrees of wider consciousness and wider powers. But they fall short of the highest levels of consciousness. This is why there is still bifurcation between Knowledge and Will. The dimensions of Knowledge and Will are in a state of disequilibrium.

6. In order to establish the right equilibrium, therefore, it is necessary to orient the mental consciousness and mental knowledge towards the dimension of Good Will.

7. The verses given in this Section provide for this extremely important direction.

Page–54